John Wilkes Booth Trail

JOHN WILKES

BOOTH

CHASING LINCOLN’S ASSASSIN

WAR ON THE CHESAPEAKE BAY

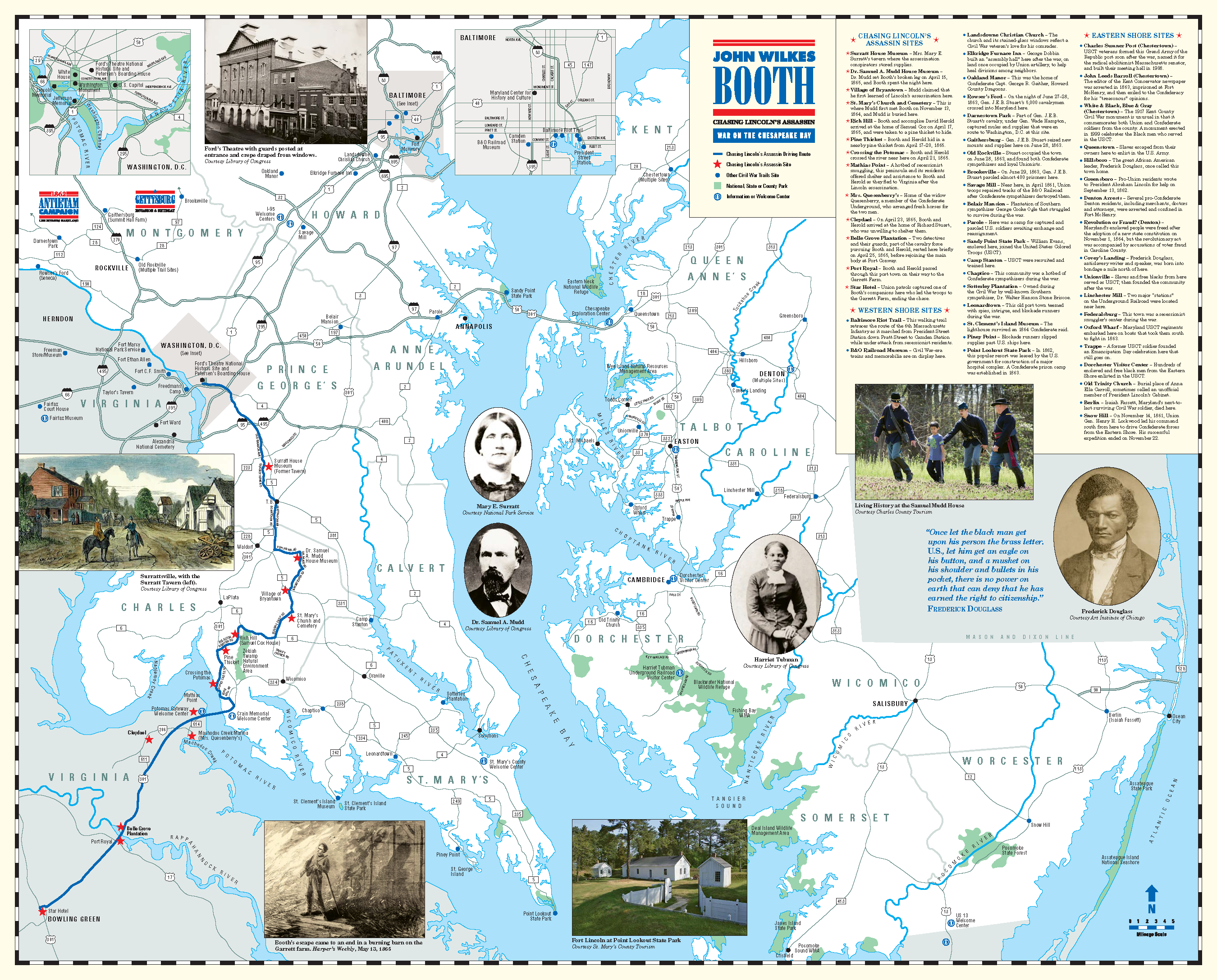

This guide depicts a scenic 90-mile driving tour that follows the route taken by John Wilkes Booth as he attempted escape after assassinating President Abraham Lincoln in April 1865. This guide also offers a collection of sites scattered throughout the southern region of the Chesapeake Bay. Follow the bugle trailblazer signs to waysides that chronicle the day-to-day tale of America’s most infamous villain and discover the Civil War’s lesser-known but important sites. Along the way, explore the landscape while paddling a waterway or while hiking or biking a trail, and experience nature and Civil War heritage up close. Parks, trails, historic sites and museums offer an in-depth look at the war on the home front, in the heat of battle, and beyond the battlefield. Take a break in nearby Civil War cities and towns for dining, lodging, shopping and attractions. For additional Civil War Trails information, visit CivilWarTrails.org and download the Maryland Civil War Trails app from Apple or Google Play to discover Civil War history and fun things to see and do along the way.

CHASING LINCOLN’S ASSASSIN

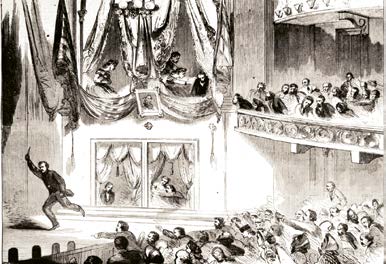

John Wilkes Booth’s plot to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln in April 1865 began as a conspiracy to kidnap him. Whether the Confederate high command in Richmond, Virginia, sanctioned the plan or Booth retaliated on his own for what he perceived as Lincoln’s harsh wartime policies is unclear. In the fall of 1864, Booth, the popular actor, arrived in Southern Maryland, a haven for Confederate sympathizers, with letters of introduction from exiled Confederates in Canada. He also brought his scheme to kidnap the President. Booth gathered recruits to assist him. By April 1865, He abandoned the kidnapping plot in favor of assassination. On April 14, shortly after 10 p.m., Booth shot Lincoln in the back of the head, while the president watched a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Booth fled over the Navy Yard Bridge into Southern Maryland. With fellow conspirator David Herold, he stopped around midnight at widow Mary E. Surratt’s tavern in the village of Surrattsville. She was then operating a boardinghouse in Washington, D.C., but a tenant at the tavern testified that Booth retrieved rifles, field glasses, and other supplies hidden there as part of the earlier kidnapping scheme. The tenant also said that Surratt had been at the tavern as recently as the afternoon of April 14, and had left instructions to have the equipment ready. His testimony was fatal to Surratt, marking the first time that the federal government had executed and hung a woman.

Booth and Herold did not linger at the tavern, but headed south to the village of T.B. and then into Charles County. Their exact route is uncertain, but their destination was Dr. Samuel A. Mudd’s home about three miles north of Bryantown. The doctor and Booth had met previously, and Mudd had introduced the actor to a leading Confederate agent, Thomas Harbin, as well as John Surratt, Jr., a Confederate courier and son of Mary Surratt. The fugitives arrived at the Mudd farm early in the morning of April 15, seeking help for the broken leg that Booth had sustained in his escape. After setting the leg, Mudd allowed the pair to rest in an upstairs bedroom. That afternoon, the doctor went into Bryantown, learned that it was occupied by Federal troops, and that the search was on for Lincoln’s assassin. Mudd returned home and sent Booth and Herold on their way. The last time he saw them, they were headed in the direction of Zekiah Swamp. Mudd was later sentenced to prison for assisting Booth.

However, the pair did not seek refuge in the swamp. They made a wide arc around Bryantown and were guided to the home of Samuel Cox (near the present-day town of Bel Alton) shortly after midnight on April 16. Cox sent them to a dense pine thicket where they hid for several days, receiving food and newspapers from Thomas Jones, a Confederate signal agent, and Franklin Robey, Cox’s overseer. On the night of April 20, Jones led the fugitives to the Potomac River where he had hidden a rowboat. He directed them to Mathias Point on the Virginia shore, but for some reason the pair rowed to Nanjemoy Creek in Maryland, where they rested before trying again the next night.

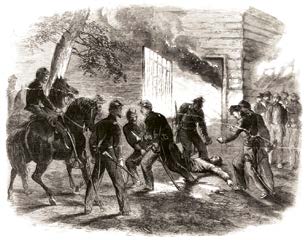

Once in Virginia, Booth and Herold crossed the Rappahannock River and found shelter at Richard Garrett’s farm. There, early in the morning of April 26, 1865, Federal troops found them hiding in a tobacco barn. Herold surrendered as ordered, but Booth refused. To force him out, the barn was set on fire. The soldiers could see Booth through the slats in the barn, and Sgt. Boston Corbett shot him in the back of the neck. Soldiers dragged Booth onto the porch of the nearby farmhouse, where he died a few hours later. Herold was returned to Washington, D.C., where he stood trial and suffered death on the gallows.

Booth limps across the stage after shooting President Lincoln. Harper’s Weekly, Apr. 27, 1865

Of those who helped Booth escape through Maryland, only Herold, Mrs. Surratt and Dr. Mudd were prosecuted. Cox, Jones, and others associated with the assassin’s flight were released after several weeks in jail. Jones wrote a book, J. Wilkes Booth (1893), about his experience.

POINT LOOKOUT

With the Chesapeake Bay on one side and the Potomac River on the other, Point Lookout was an ideal location for the Federal government to construct a state-ofthe-art hospital and the North’s largest prisoner-of-war camp, because it was remote, and yet easily accessible by boat. Once a fine bathing beach, the pleasant retreat scene changed dramatically in 1861.

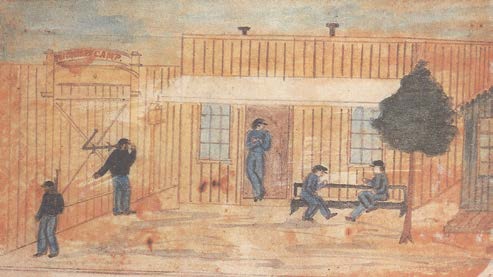

Sketch of entrance to the prison camp at Point Lookout. Courtesy Maryland Department of Natural Resources

A year after the war began, the federal government leased the Point Lookout Resort for an army hospital. Hammond General Hospital, built like the spokes of a wheel, received its first wounded patients on August 17, 1862. Early in 1863, a small number of prisoners were confined to the hospital grounds. Many of them were Southern Marylanders accused of assisting the Confederacy. Today, most of the hospital site lies underneath the Chesapeake Bay.

Soon after the capture of thousands of Confederates at the Battle of Gettysburg, construction began on Camp Hoffman, which was capable of holding 10,000 prisoners of war. As the war progressed and prisoner exchanges ceased, the camp became overcrowded, with more than 20,000 men confined by June 1864. At the height of the war, the lack of sanitation contaminated the wells and some men froze to death in tents, having but one blanket and very little wood for fire. More than 4,000 men died.

The prisoners occupied themselves making trinkets they bartered, since money was scarce. A school was organized to teach the “three Rs,” and church services were held in an old building. By the time the war ended, more than 52,000 prisoners had passed through Camp Hoffman’s gates. Today, a small section of the prison pen has been reconstructed where it once stood.

Three forts were erected to protect the point and prison from Confederate invasion. The earthen walls of one, Fort Lincoln, remain intact, and the rest of the fort has been reconstructed.

In 1965, a century after the war ended, Maryland’s Park Service created the 1,046–acre Point Lookout State Park. The Civil War story is told in the park’s Visitor Center exhibits.

SPIES & SMUGGLERS

To keep Maryland from seceding when the Civil War began in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln ordered Federal troops to occupy the state. He also suspended the writ of habeas corpus, and jailed suspected Confederate sympathizers, including public officials, newspaper editors, and private citizens. Had Maryland seceded, Confederate territory would have surrounded Washington, D.C.

Though many Maryland men served in the U.S. Army, thousands of others enlisted in Confederate service. Southern partisans who stayed home conducted signal corps operations, ran the federal blockade to deliver vital supplies, and engaged in espionage. Southern Maryland was a hotbed of “secesh” intrigue, and many famous Confederate spies had ties to this region.

Perhaps the most famous Confederate spy, Maria Rosetta O’Neale Greenhow, known as “Rebel Rose,” was born in Southern Maryland about 1814. An antebellum social leader in Washington, D.C., Greenhow used her connections to elicit critical information from federal officials and military figures. In July 1861, aided by another Marylander, Betty Duvall, Greenhow delivered a coded message detailing Union plans for the First Battle of Manassas to Confederate Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard. Confederate President Jefferson Davis credited Greenhow with the ensuing victory.

In August, federal officials placed her under house arrest, but she continued to spy. That autumn, she was confined in the Old Capitol Prison, on the present site of the U.S. Supreme Court, and then sent to Richmond. She spent time in Europe and wrote her memoirs, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington. Greenhow sailed in a blockade runner for North Carolina in 1864, but the ship sank off Cape Fear and she drowned. She is buried in Wilmington, N.C.

Another Maryland spy, Olivia Floyd, conducted her espionage activities from Rose Hill, her home in Port Tobacco, using her charm to extract information from Union officers. After the war, she was the guest of honor at a Confederate veterans’ reunion in Kentucky.

Maria Rosetta O’Neale Greenhow. Courtesy Library of Congress

Pro-Confederate residents of Southern Maryland not only gathered military intelligence but also food, supplies, and medicine. Sick and hungry Confederate soldiers who slipped into Southern Maryland got help from sympathizers. According to local tradition, young Catharine Hayden, known as the Angel of Chaptico, provided Confederate soldiers with food and medicine she obtained from her uncle, a physician. She suffered an epileptic seizure on Christmas Day 1872, fell into a fireplace, and died the following day. For years, her family received letters from all over the South from veterans who had learned of her tragic death. She is buried at Christ Church in Chaptico.

AFRICAN AMERICANS ENLIST

Company of the 4th USCT, one of several infantry units formed in Maryland. – Courtesy Library of Congress

When President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, followed in May 1863 by establishing the United States Colored Troops (USCT), he sealed the fate of the “peculiar institution” of slavery. Although Maryland would not emancipate its 87,000 slaves for almost two more years, the enslaved liberated themselves by the thousands to join free African Americans in the United States Army and Navy.

Masters jailed slaves to prevent escape or recruitment

by Union troops; those who fled risked reprisals on family members left behind, and those who were caught were sometimes tortured or killed. Even free Blacks were barred from enlisting until October 3, 1863, when the USCT began recruiting in Maryland. Slaveholders were offered compensation for any person who enlisted with or without his master’s consent.

Enlist they did. Despite inequality in pay and rations, segregated units, and extra danger on the battlefield— Confederates sometimes massacred, wounded, and captured Black troops— African Americans enlisted, served with honor, and fought in significant engagements.

In February 1864, a USCT company encampment at St. Johns College in Annapolis inspired more than 100 enslaved persons to enlist. Most joined the 30th and 39th Regiments and later served in the Wilderness Campaign, the Siege of Petersburg and the Battle of the Crater, and the Capture of Richmond.

African Americans from Maryland’s Eastern Shore also served with distinction; three of whom received the Medal of Honor. In Talbot County, the town of Unionville was founded in 1867 by 18 USCT veterans whose graves are located in the cemetery of St. Stephens A.M.E. Church. In Kent County, more than 400 Blacks joined the USCT, and many perished. Surviving veterans established an integrated Charles Sumner Post in Chestertown that served them and their families for more than a century.

Harriet Tubman, born in Dorchester County, served as a scout for the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers. Other AfricanAmerican women became nurses and spies. Two sons of Frederick Douglass, a Talbot County native, served as commissioned officers.

In all, 8,718 Maryland African Americans, both enslaved and free, joined the USCT. Many others joined the U.S. Navy. After President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, USCT were among those dispatched to search the Southern Maryland countryside for his killers.

PRESERVING THE UNION

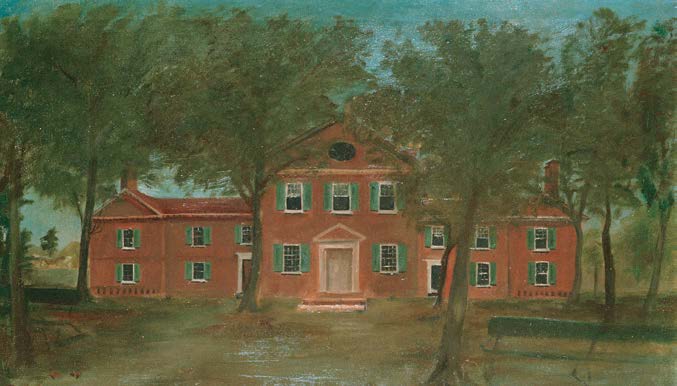

Caroline County Courthouse

During the Civil War, the federal government took drastic and controversial steps to keep Maryland in the Union, arresting newspaper editors and even state and local officials suspected of Confederate sympathies. For example, on May 26, 1862, Deputy U.S. Marshal John S. McPhail and Special Officer John L. Bishop entered the Talbot County courtroom in Easton and arrested Judge Richard Bennett Carmichael. The judge had been an outspoken opponent of the presence of Federal troops at Eastern Shore polling places during local elections in 1861, which he believed intimidated voters. Carmichael asked by what authority McPhail and Bishop disrupted the proceedings, and they replied, “By the authority of the United States.” Carmichael resisted, and Bishop beat him unconscious. Prosecuting attorney Isaac C.W. Powell tried to help Carmichael and was also arrested. Carmichael and Powell were transported to Baltimore and served a six-month confinement at Forts McHenry, Lafayette, and Delaware, but were never formally charged. Carmichael twice wrote President Abraham Lincoln but received no reply.

THE CHASE ENDS

John Wilkes Booth’s flight from justice ended at the Richard Garrett farm south of Port Royal on April 26, 1865. The 16th New York Cavalry, acting on a tip, found Booth and accomplice David Herold hidden in a tobacco barn there. Herold surrendered but Booth refused, even after the troopers set the barn afire to flush him out. Sgt. Thomas P. “Boston” Corbett claimed he shot Booth through a crack in the wall as he was about to fire his weapon. Booth was dragged out and died on the farmhouse porch. Corbett was arrested for violating orders to take Booth alive, but the charge was dropped and he became a national hero. The Garrett Farm buildings are long gone, and the site, part of Fort A.P. Hill, is not accessible to the public

Wounded Booth pulled from the burning barn, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, May 13, 1865

TRAVEL RESOURCES

Maryland Office of Tourism Development

401 E. Pratt Street 14th Floor Baltimore, MD 21202 (866) 639-3526 VisitMaryland.org

Annapolis & Anne Arundel County Convention & Visitors Bureau

26 West Street Annapolis, MD 21401 (888) 302-2852 VisitAnnapolis.org

Caroline County Office of Tourism

10219 River Landing Road Denton, MD 21629 (410) 479-0655 VisitCaroline.org

Charles County Office of Tourism

8190 Port Tobacco Road Port Tobacco, MD 20677 (301) 645-0610 CharlesCountyMd.gov/tourism

Point Lookout State Park

11175 Point Lookout Road Scotland, MD 20687 (301) 872-5688 dnr.maryland.gov/publiclands/ Pages/southern/pointlookout. aspx

Dorchester County Tourism

2 Rose Hill Place Cambridge, MD 21613 (410) 228-1000 VisitDorchester.org

Howard County Tourism & Promotion

8267 Main Street Ellicott City, MD 21043 (410) 313-1902 VisitHowardCounty.com

Kent County Office of Tourism

400 High Street Chestertown, MD 21620 (410) 778-0416 KentCounty.com

Prince George’s County Conference & Visitors Bureau

9200 Basil Court, Suite 101 Largo, MD 20774 (301) 925-8300 VisitPrinceGeorges.com

Talbot County Office of Tourism

11 S. Harrison Street Easton, MD 21601 (410) 770-8000 TourTalbot.org

The Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail on the Potomac River offers a great way to connect with nature and get some exercise. Here kayakers launch from. Piscataway Park. – Courtesy the Accokeek Foundation

Dr. Samuel A. Mudd House Museum

3725 Dr. Samuel Mudd Road Waldorf, MD 20601 (301) 274-9358 DrMudd.org

St. Mary’s County Tourism

23115 Leonard Hall Drive Leonardtown, MD 20650 (800) 327-9023 VisitStMarysMd.com

Surratt House Museum

9118 Brandywine Road Clinton, MD 20735 (301) 868-1121 SurrattMuseum.org

Worcester County Tourism

104 West Market Street Snow Hill, MD 21863 (800) 852-0335 VisitWorcester.org

Queen Anne’s County Tourism

425 Piney Narrows Road Chester, MD 21619 (410) 604-2100 VisitQueenAnnes.com

Maryland Civil War Trails Mobile App

play.google.com apple.com